Fragments for a history of Galapagos

Pirates, whalers, settlers and scientists

The Galapagos Islands are a place with a unique human history, which oscillates between the strange and the tragic: legendary Inca sailors share the pages of the Galapagos chronicles with Spanish conquerors, English pirates and buccaneers, American whalers, Ecuadorian prisoners and foremen, Robinsons and castaways... And, almost inevitably, with Darwin, the Beagle, and dozens of other scientific expeditions.

The relationship of human beings with the archipelago was never simple. The first Spanish navigators called them "Enchanted islands": unable to place them on their charts, they believed they were enchanted, that is, subject to an evil charm that made them appear and disappear. Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick (and a crew member of one of the many whaling boats that fished in the Galapagos) immortalized that ancient name in one of his best literary works, The Encantadas (1854). His description of the islands was not exactly flattering: he referred to them as "five-and-twenty heaps of cinders" in the middle of the sea.

The reputation of "enchanted" that the islands had among the Spanish during the Latin American colonial period allowed buccaneers and pirates to make them their refuge during the 17th and 18th centuries; in fact, the author of the first reliable map of the archipelago was an English privateer, William A. Cowley (1684).

A century later, after the end of the era of pirates, the place of those famous outlaws was taken by whalers and sea lion hunters, who abused local natural resources to the point of the almost extinction of some species. Thirty years after their arrival, when the sperm whales, seals and giant tortoises had practically disappeared, and the iguanas and penguins were seriously threatened, the hunting and fishing vessels left the area and headed to devastate other lands and other waters. The Galapagos then became part of the Ecuadorian national territory (1832) and, after Darwin's visit in 1835, a place of study and research.

During the last part of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, countless scientific expeditions visited the islands. And paradoxically, they predated its fauna and flora to inconceivable levels, to feed the almost insatiable hunger for specimens from the zoos, museums, and private natural history collections of Western Europe and North America. At the same time, a good number of Ecuadorian settlers came from the mainland to work, under semi-slave conditions, for ruthless landowners. Thus, by 1930 the degradation of the Galapagos landscapes was brutal. In addition to the damage caused by introduced animals (dogs, cats, goats, pigs, rats), the overexploitation of resources by settlers had brought most of the endemic species to the brink of extinction.

In 1958, the enormous concern openly expressed by the international scientific community in relation to Galapagos biodiversity led to the creation, by the government of Ecuador, of the Galapagos National Park. The Park was officially inaugurated on July 20, 1959, and since then it has protected 97% of the archipelago's land surface. Three days later, and with the support of UNESCO and the IUCN, the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands (CDF) was created in Brussels to support (inter)national efforts to conserve the islands.

In 1960, and under particularly harsh conditions, the CDF began to build a scientific station near Puerto Ayora, on the southern coast of Santa Cruz Island. Inaugurated on January 20, 1964, the Charles Darwin Research Station (CDRS) immediately became a space where scientists and researchers developed their projects, trying to describe and understand Galapagos ecosystems and, at the same time, identify threats to their survival.

From that moment, the CDRS grew to become a modern and well-equipped institution in which an international team of professionals carries out its activities. And, at the same time, it became the place where the entire history of such work is preserved: the great and small narratives of scientific achievements, but also the social memory of the protection and conservation of Galapagos, with all its efforts, struggles, successes and failures through the decades.

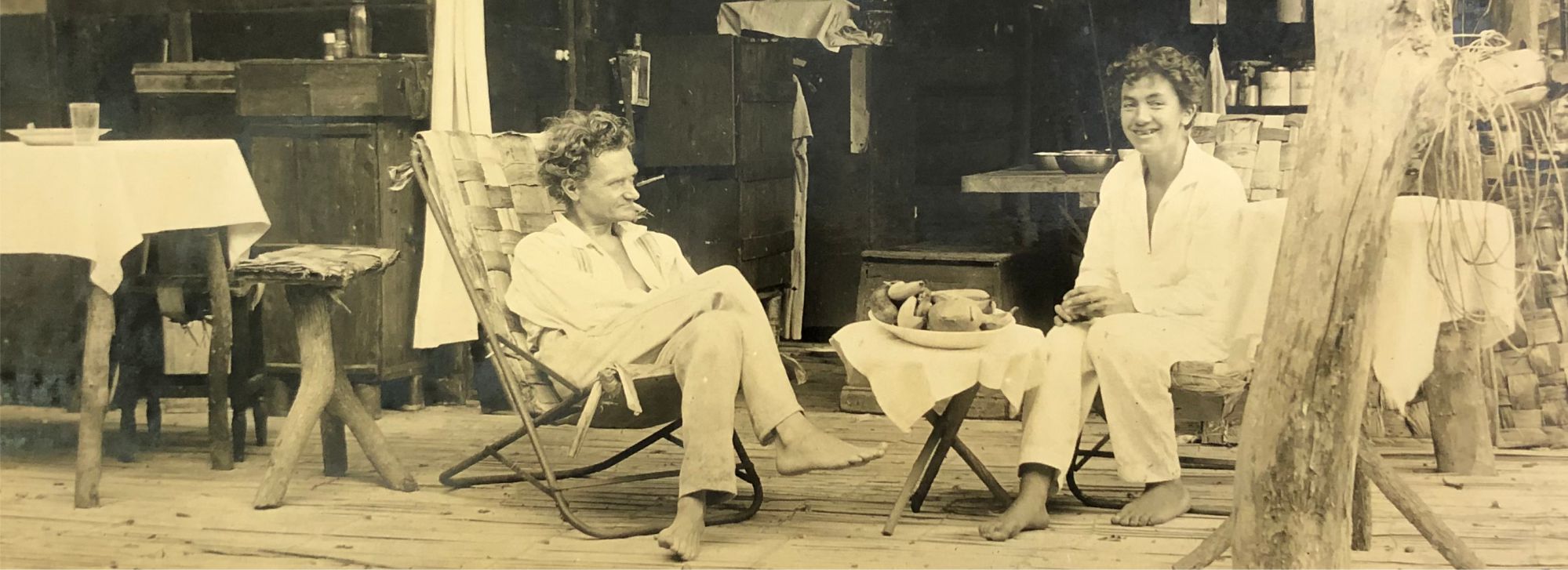

[The photograph that illustrates this text is included in the "Nourmahal" album. It is labeled "Dr. Ritter and 'Dore' 'at home'. Charles Id., Galapagos. April, 1932. Gift of H. S. Swarth" and is a later addition to the Nourmahal Expedition's visit to Galapagos in 1930].

References

Melville, Hermann (2002). The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles. London: Hesperus.

Text & picture: Edgardo Civallero (edgardo.civallero@fcdarwin.org.ec).

Publication date: 1 December 2021

Last update: 1 December 2021