Letters from the library

#11. Hunting the wild bull

Not everything we store in our archives and libraries displays trustworthy information or reliably documents an event. There is, in our knowledge and memory repositories, a lot of information that is far from being "true".

And yet, even knowing it, we keep it. Because these documents reflect a very particular way of seeing, understanding and explaining the world. One that, while not always being "the truth," at least makes an effort to capture reality in a credible way.

A paradigmatic case is the one we keep in the CDF Archive. It is a newspaper page, yellowed by the years and the acidity of the paper, and framed as if it were an art masterpiece, in a probable attempt to protect it from the natural decomposition to which these materials are subjected.

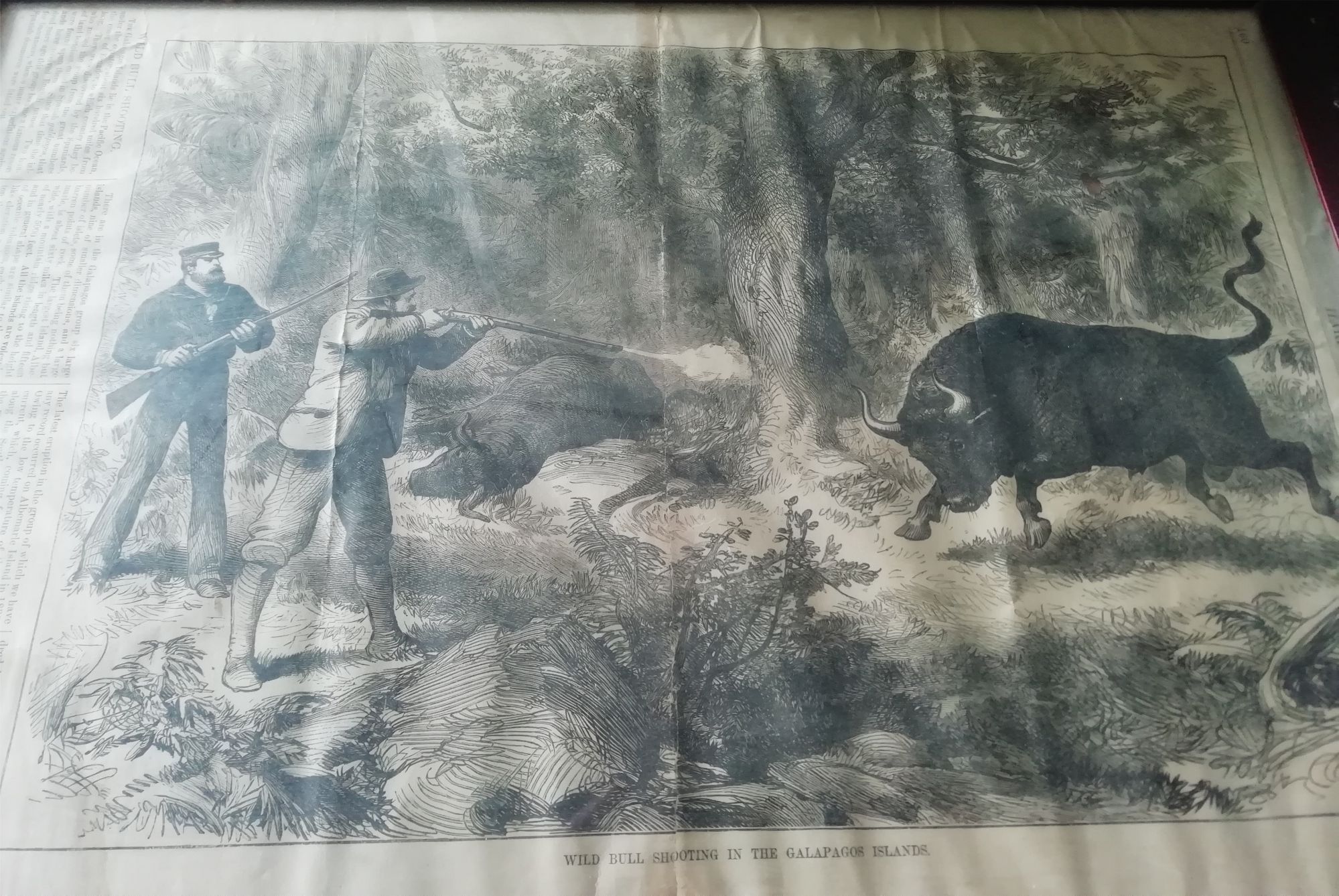

It is a page from Harper's Weekly, a magazine published in New York between 1857 and 1916 and subtitled "A Journal of Civilization." The piece belongs to the supplement dated February 24th, 1877, and includes a huge engraving, and three paragraphs printed at the bottom.

The engraving represents the "bull hunt" in the Galapagos.

In it, we are shown a Spanish fighting bull that seems to have escaped from the Sanfermines of Pamplona or the Maestranza in Seville, charging two men dressed as explorers of Africa in the 19th century, in a forest that could very well be located in the American Rocky Mountains, or being an oak grove in Victorian England.

Obviously, the image was produced by an artist who had never set foot in the Galapagos and who was given the title of the illustration and little else. In a time when photography was an incipient technique and when transporting a camera to the "Encantadas" would have been quite an adventure (a very expensive one, too), there was no other solution than to use one's imagination... and, hopefully, some travelers' notes.

Can we blame them? The editors tried to convey to their readers a vivid picture of the events. And no matter how distant that image was from reality, I am more than sure that it achieved its goal.

The accompanying text, fortunately, provided Harper's Weekly's subscribers with more accurate information. Much more, by the way, than some current texts on the archipelago.

WILD BULL SHOOTING

The Galapagos Islands lie in the Pacific Ocean, under the equator, about six hundred miles from the coast of Ecuador, to which country they belong. They were discovered by the Spaniards, who named the group from the great number of land tortoises, called in Spanish galápagos, that were found upon them. Since that time the islands have received English names. Two hundred years ago this group became a famous resort for buccaneers, whence many expeditions against Spanish commerce were fitted out.

There are in the Galapagos group six large islands, nine of smaller dimensions, and a large number of islets, some of them being nothing but barren points of rock. The largest island, Albemarle, is about sixty miles in length and fifteen wide, with a mountain ridge rising to the height of nearly 5000 feet. All the islands are volcanic, and in general shape are similar to the majority of oceanic volcanoes, each having a large dome-like elevation, with a wide, shallow crater at the top, the sides furrowed by the streams of lava that once overflowed from the crater. Volcanic activity has apparently ceased on all these islands. The latest eruption in the group of which we have any record occurred in Albemarle Island in 1835. Owing to the low temperature of the Peruvian current, which, coming from antartic regions along the South American coast, strikes out to the westward toward these islands, the climate of the Galapagos is very mild, considering their position directly under the equator.

The Galapagos were first permanently settled in 1832 by a party of exiles from Ecuador, who were sent to Charles Island, one of the most fertile of the group. At one time the settlement contained between two hundred and three hundred inhabitants, but the number has dwindled down, until a few miserable peons hold possession. Cattle, pigs, and goats were sent to the islands with the early settlers. They have greatly increased in numbers, roaming wild in the forests, and afford excellent sport to persons who chance to land there on the rare occasion of a ship stepping to procure a supply of turtles. These were once so abundant that a single ship has been known to carry away as many as seven hundred, but of late years they have greatly diminished in number, in consequence of being overhunted, and large ones are rarely found.

Memories are like that: interlocking fragments of information that try to leave as indelible a mark as possible. It does not always matter that these fragments have a weak foundation: the really important thing is to plant a sign that allows us to remember. Somehow.

And here we are, almost a century and a half later, remembering that at some point in the past "bulls" were hunted in the Galapagos. And imagining the astonished faces of those nineteenth-century New York readers, sitting comfortably in their living rooms, imagining a reality that they would never step on but that, thanks to that illustration, entered their consciousness.

And into their memories.

Keywords: History of Galapagos

Subject categories: Artifacts | Invasive species | Memory | Newspapers

Time framework: 1877

Text & picture: Edgardo Civallero (edgardo.civallero@fcdarwin.org.ec)

Publication date: 1 February 2021

Last update: 1 November 2022