Letters from the library

#12. With a little sea lion on the lap (II)

Almost two years ago, in the third installment of this series of letters, I wrote that the oldest collection of photos in the CDF Archive to date is the so-called "Nourmahal album", a set of paper-based photographs taken in 1930. I said that the USS Nourmahal was a ship of about 80 m in length, built in 1928 as a pleasure yacht for the American billionaire Vincent Astor. I commented that between March 23 and May 2, 1930, Astor brought a group of American scientists —researchers from the New York Aquarium, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Brooklyn Botanical Garden— to Galapagos, on an expedition for collecting samples. I ended by mentioning that the "Nourmahal album" showed details of that journey, and that one of the most curious images in it was the one of a sailor holding a sea lion pup on his lap.

In that post I spoke about the magic of archives: places that allow us to travel to other times and places, opening doors and windows that put us in contact with realities and unique moments — moments long gone but that come back to life, for an instant, in front of our eyes. I concluded that text by pointing out that we would probably never be able to know the name of the sailor or the origin or destination of the little sea lion.

However, documents —photos, manuscripts, articles, films, artifacts— are rarely born in isolation, devoid of connections. Those of us who work in libraries, archives and museums know, from our own experience, that we handle a mesh of knowledge and memories: a dense fabric made up of thousands and thousands of threads that intersect to compose what we call "memory", which in turn defines what we know as "identity" and allows us to build that subjective and variable narrative we call "history."

The documents that populate our archives have links, often invisible, with many others. Discovering those connections, those tenuous threads that interweave discourses and stories, allows us to understand a particular item within the framework of a much broader and richer context. A ring of those used to mark birds is just that, a ring, with no more history than its function. Until a catalogue card appeared in a forgotten corner of the archive links that small cylindrical piece of plastic with the research of a famous ornithologist specializing in finches, and with a particular trip, and with some field notes, and with an article or a thesis, and with some photographs... By getting a context, the plastic ring ceases to be a simple little artifact without a history, and becomes part of a web of memories.

It becomes one more strand of the fabric.

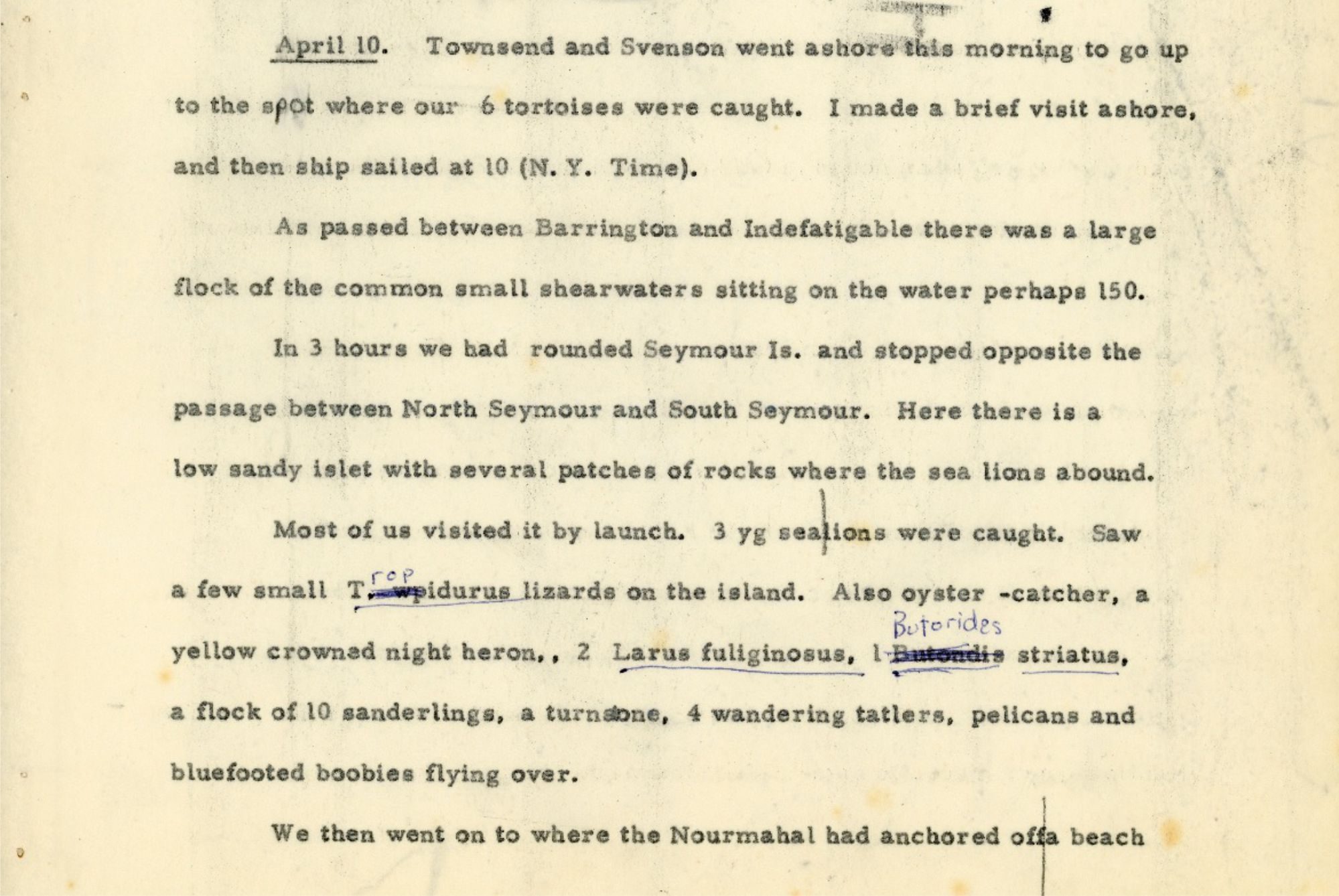

That is what happened recently with the photo of the sea lion pup. Reviewing the special collection of the CDF Library I discovered, a few months ago, a typewritten copy of the field diary of one of the scientists who participated in the Nourmahal's trip to Galapagos. The careful notes reflect the day-to-day life of that researcher, an American ornithologist at the American Museum of Natural History. And among them appears the following, noted on April 10, 1930:

In 3 hours we had rounded Seymour Island and stopped opposite the passage between North Seymour and South Seymour. Here there is a low sandy islet with several patches of rocks where the sea lions abound. Most of us visited it by launch. Three young sealions were caught.

There is no other mention of captures of sea lions in the entire diary. Thanks to some writings scribbled in a field notebook almost a century ago, I found out that that pup in the photo of the "Nourmahal album" was born on that strip of sand that we call "Mosquera Islet", between the Seymour Islands.

If I pulled on that strand, I could probably track the animal, and know where its days ended. I could even find out the name of the sailor who held it in the picture. Because his role, ship's carpenter, appears in the same diary, in the entry for May 1, 1930:

Photos of menagerie on upper deck. Bronson drawing legs of tortoise (suspended). Ship's carpenter holding sea-lion.

This is how dense and rich are the memory frames that are woven inside the archives.

Although sometimes the threads are lost, or destroyed, and with them part of the fabric, the context, and the memory disappears. Hence the vital importance of archives. And of each and every one of the materials that those archives treasure.

[See also: On the Nourmahal].

Subject categories: History of Galapagos | History of science | Natural history

Keywords: Expeditions | Memory | Photos | Travels

Time framework: 1930

Text & picture: Edgardo Civallero (edgardo.civallero@fcdarwin.org.ec)

Publication date: 1 June 2021

Last update: 1 November 2022