Letters from the library

#16. Story of a death in a duel with pistols

It is well known that the Galapagos Islands are worthy of some dark pages ―one could even say macabre― in the Great Book of History: The deeds of Briones (the "Pirate of the Guayas"), the uprising of the workers of Floreana and San Cristóbal islands against their employers, the cruel penal colonies, the still unresolved disappearances in Floreana, the shipwrecks and their stories of survival... Death, like everywhere else, lurks around the corner on the islands; however, in this somewhat magical and somewhat desolate territory, it seems to acquire novelistic overtones.

An episode not too well known included within those sad annals of the archipelagic history is that of the duel of Officer Cowan. That name, Cowan, was immortalized in the Galapagoan geography ― specifically, in a bay, a cape and a volcano located on the northwestern coast of Santiago Island. However, very few know the origin of that name. Something that, to be honest, could be said of a good part of the islands' place names.

History forces us to go back in time to the mid-nineteenth century, the time when European and American whalers and furriers conscientiously plundered the coasts and currents of the Atlantic and, faced with their evident exhaustion, sought new territories and virgin spaces where to sink the fangs of their greed. The Pacific, the vast South Sea, a true terra incognita until a century before, was the perfect candidate, so the great powers began to compete for the control of those waters. The newly independent American nations had a certain advantage, since they controlled the eastern shores of that Ocean, but that was not going to discourage countries like Great Britain or the United States, used to get what they wanted the good or, more often, the bad way.

In 1813, American captain David Porter arrived in the Galapagos, commanding the U.S.S. Essex, with the purpose of "cleansing" the region of British whalers (the competition) and assessing its value as a hunting ground. Porter travelled the archipelago, captured several English ships and, in his diary, gave an account of the necessary details... and many more: back then, as it is still the case today, the American seaman was unable to hide his amazement at the wonderful biodiversity that paraded, unconcerned, in front of his eyes.

In that same diary (published in 1815), the captain gave the account, very casually and even concealing the terms, of a duel. The fact was not allowed within the British navy (Porter himself mentions it as "a practice which disgraces human nature"), but it was the usual custom of the time: to resolve differences with knives, sabers or pistols. The reason for the dispute was not recorded by Porter, but apparently it occurred between two of his officers, who landed in James Bay, in Santiago, in broad daylight, surely accompanied by their trusted people, and tried to settle their problems with gunpowder and lead.

As a result, one of the officers, Lieutenant John S. Cowan, was killed by the third shot. He was buried by Porter in the vicinity of a spring that was then widely used by sailors passing through the Galapagos, which is still located at the foot of the hill known as "Pan de Azúcar". The following inscription was placed on his grave:

Sacred to the memory

of Lieut. John S. Cowan,

of the U.S. Frigate Essex,

who died here anno 1813,

aged 21 years.

His loss is ever to be regretted

by his country;

and mourned by his friends

and brother officers.

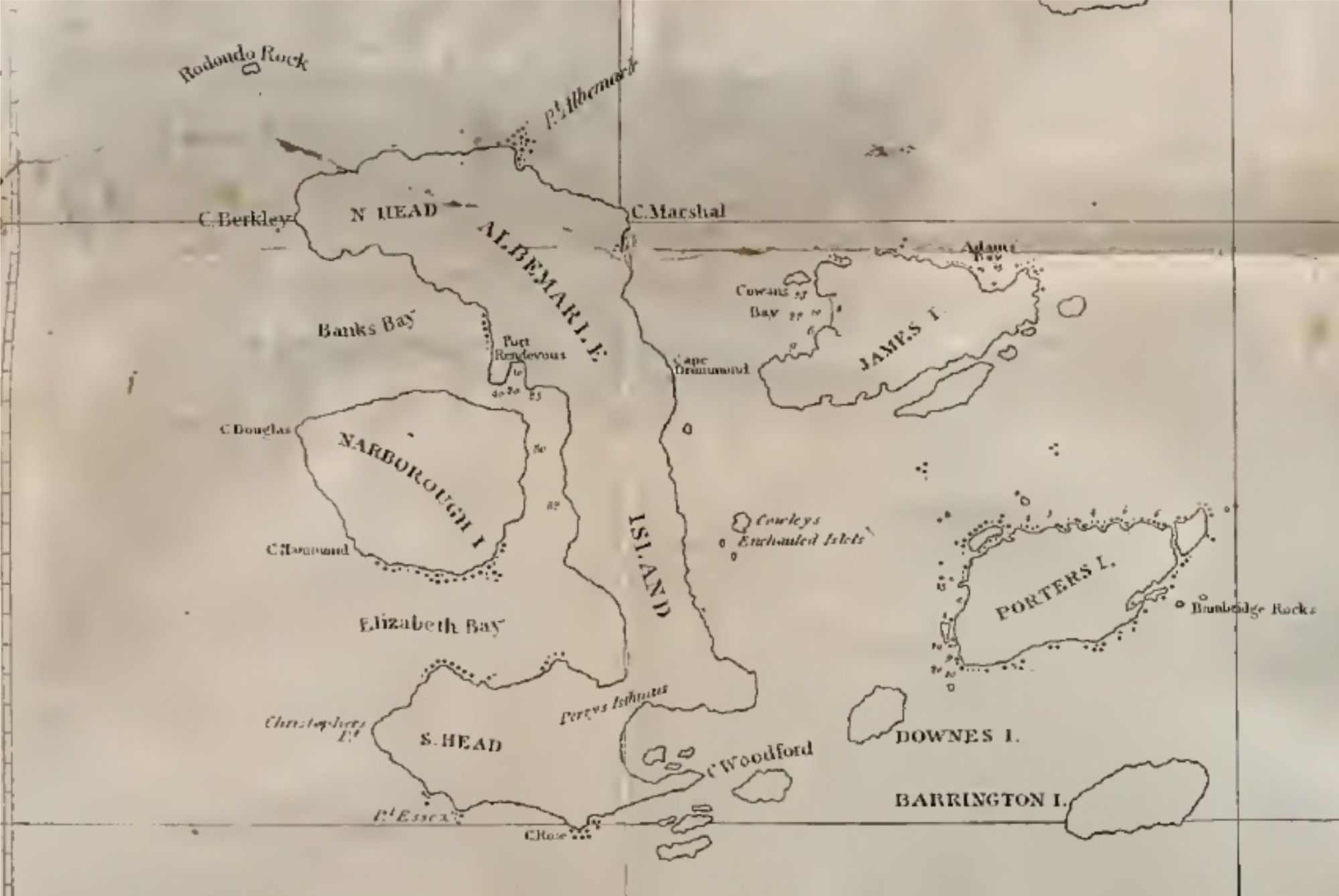

In the map of the islands that he made to document his journey (and which was published only in the second edition of his diary, in 1822), Porter used the surname of his subordinate to name a bay, "Cowan's Bay", open to the west of Santiago, inhabited by boobies and frigatebirds, soaked by the island's drizzles and always bristling with the blowing of the winds. The name seems to have spread, later, to the cape and to the mountain.

For some time, Cowan's tomb became a visitor's site: a kind of place of pilgrimage, a true landmark in the landscape of Santiago Island. In fact, the cross that marked its location is mentioned by several chroniclers and travelers for at least half a century after the duel took place (an example are the notes of naturalist John Scouler, in 1825). However, at a certain point it seems to have disappeared, since no one mentions it again...

...until 1965. Then, Norwegian settler Jacob Lundh, one of the first inhabitants of what is now Puerto Ayora and "unofficial historian" of the islands (in addition to being the original owner of the land where the Charles Darwin Research Station stands today) wrote a short text for the Charles Darwin Foundation entitled Notes on the Galápagos Islands. There he wrote down a story that, apparently, circulated among the old workers of the salt mine that, from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, operated in Santiago. Lundh, quoting the words of Hugo Egas Zevallos (son of Darío Egas Sánchez, original owner of the west side of the island and of the mine), said that, in 1926, the salt workers had found, near the spring of "Pan de Azúcar", a mummified corpse.

A corpse still wearing the remains of a blue uniform with gold braid. The uniform of British naval officers.

They said that when they touched it, the fabric fell apart. No one was sure that this was Cowan's body. But... can we speak of certainties in the legendary history of Galapagos?

Keywords: History of Galapagos

Subject categories: Books | Memory | Travels

Time framework: 1813

Text & picture: Edgardo Civallero (edgardo.civallero@fcdarwin.org.ec)

Publication date: 1 June 2022

Last update: 1 November 2022